In 2024, I journeyed through 65 books that transported me to unfamiliar places, introduced me to unforgettable women and characters, and deepened my understanding of the world, its people, and myself.

The perennial question of “What was your favorite book?” feels almost impossible to answer, especially when reading so widely and diversely. Of the 65 titles, 62 were penned by women, and 20 were translated from languages as varied as Catalan, Arabic, and Korean. My year balanced contemporary works with literary treasures from the past, including a 1928 novel and a 1938 memoir.

It was a year of revisiting beloved authors such as Elif Shafak, Yōko Ogawa, and Isabel Allende; finally dusting off books by Pearl S. Buck, Han Kang, and Lauren Groff; and discovering new favorites, including Elsa Morante, Eva Baltasar, and Tsitsi Dangarembga—writers whose works I’m eager to explore further in the coming year. Each book wove a unique thread into the tapestry of my reading life, reaffirming the transformative power and sheer joy of literature.

Throughout the year, I shared monthly reading round-ups for paid subscribers, a tradition I’ll continue in 2025. But to honour the writers and works that kept me company through 2024—many stealing hours far past my bedtime—I’ve compiled my top five picks in fiction, memoirs & biographies, and non-fiction. Each of these gems deserves a spot on your 2025 reading list.

Fiction

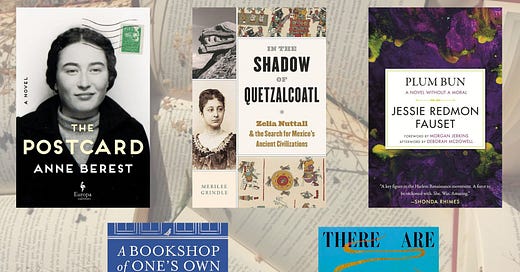

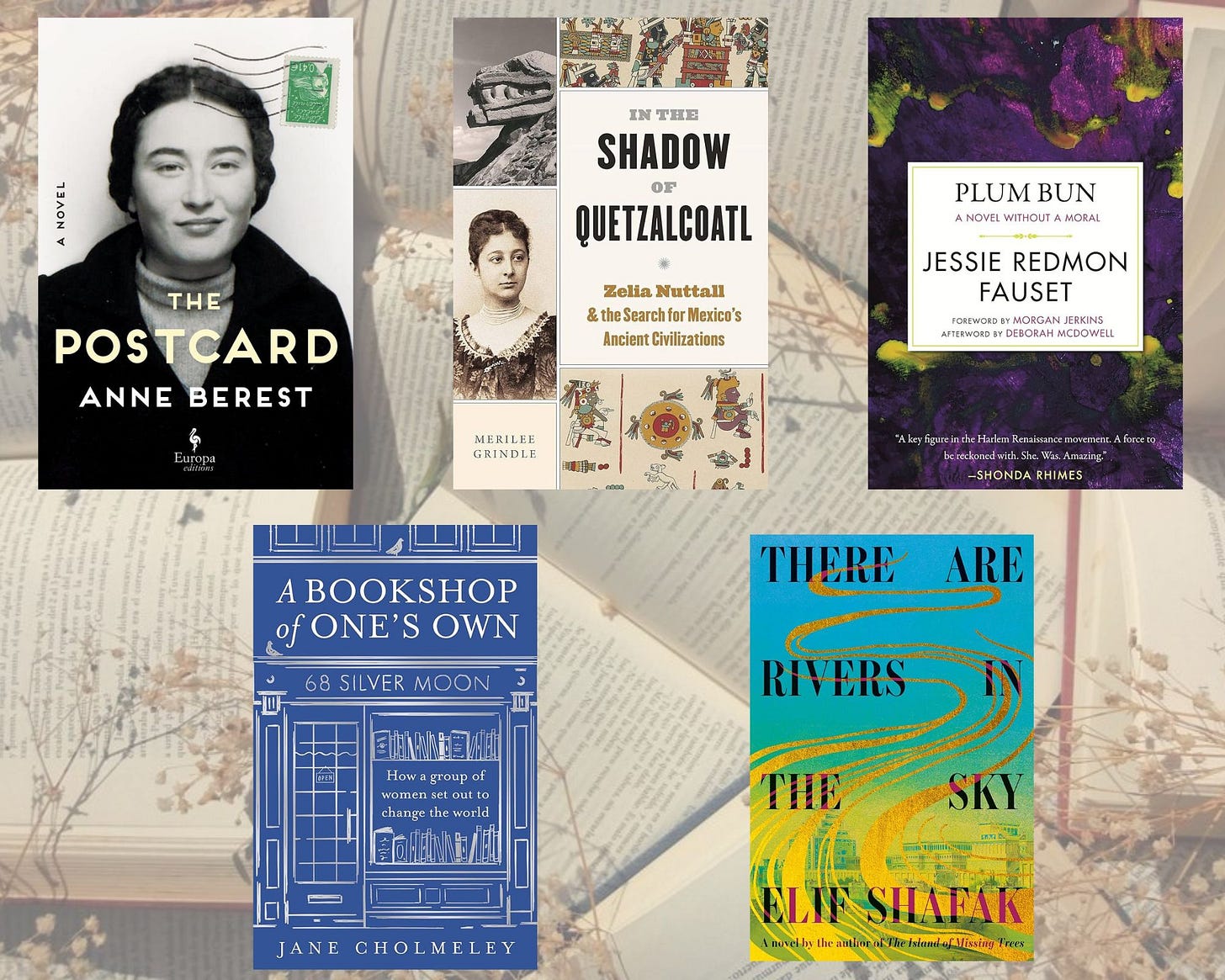

📚 The Postcard by Anne Berest, translated from the French by Tina Kover (2021, 2023 in English).

Anne Berest’s The Postcard is an evocative and intricate exploration of memory, identity, and family secrets, told through a series of fragmented narratives that span generations. The novel begins with a postcard—a seemingly innocuous artifact that, over time, unravels the story of a Jewish family whose lives were shaped by both personal and collective histories. Set in the years following the Holocaust, Berest deftly weaves together the past and present, creating a compelling tapestry of grief, survival, and discovery. Her prose is tender yet unflinching, capturing the emotional weight of a family’s quest for answers while confronting the spectre of a painful legacy.

Berest’s ability to balance historical reflection with a deeply personal journey makes The Postcard particularly powerful. As the protagonist uncovers the layers of her family's hidden truths, the novel takes on a reflective quality. It explores the lasting impact of trauma and the subtle ways in which history reverberates through the generations. The book is both a meditation on loss and a tribute to resilience, offering a poignant and immersive reading experience that lingers long after the final page.

📚 The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith (2007, 2016 in English).

This title, by the 2024 Nobel Prize Winner for Literature, has been on my to-read list for years, and I’m still baffled by why it took me so long to finally dive in—though, as is often the case, these things happen. Winner of the 2016 Man Booker International Prize, The Vegetarian tells the compelling story of Yeong-hye, a woman whose decision to stop eating meat becomes an act of defiance against the deeply ingrained societal norms and familial expectations in South Korea. It is a striking exploration of agency and the consequences of choosing to reject conformity.

The novel’s structure, divided into three parts, each narrated from a different character’s perspective, shows the ripple effects of Yeong-hye’s transformation. The prose is poetic yet haunting, delving into themes of mental illness, societal pressure, and the cultural impulse to control women. It’s the kind of book that lingers long after the last page, making its way onto my list of top books of 2024. I also highly recommend watching this interview with Kang, which one of you kindly recommended to me—it adds another layer of insight to an already remarkable read.

📚 Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928).

The novel follows the life of its protagonist, Angela Murray, as she navigates the complexities of being a light-skinned Black woman in a world divided by race. Fauset’s prose is both elegant and piercing, capturing Angela’s internal struggle as she grapples with the tension between her desire for upward mobility and the societal pressures to conform to racial expectations. The book deftly examines themes of colorism, class, and the elusive nature of identity, offering a nuanced portrayal of the challenges faced by African Americans during this pivotal period in history.

What sets Plum Bun apart is Fauset’s ability to blend social critique with personal narrative, creating a story that is as much about the broader cultural landscape as it is about the individual’s place within it. Fauset’s characters are rich and multifaceted, and the novel’s portrayal of the Harlem Renaissance offers an insightful glimpse into the intellectual and artistic ferment of the time. While the title may suggest a lack of moral direction, the novel is anything but morally indifferent—it is a thought-provoking meditation on the ways in which race and identity intersect with ambition and self-realization.

📚 There Are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak (2024).

Elif Shafak’s latest novel is vying for the top spot on my list of favorites this year. At over 460 pages, this epic seamlessly weaves intricate, emotional narratives across time and space, going far beyond the typical scope of a sweeping tale. The story spans three timelines—1840s London/Iraq, 2014 Turkey/Iraq, and 2018 London—united by an ancient book, Nineveh and Its Remains (1848), and a symbolic journey of a single drop of water. Shafak explores universal themes of water, survival, and displacement, with each character seeking meaning in a fragmented world, their fates intertwined by the search for belonging and solace.

The lyrical prose blends history, myth, and literature, reflecting on life's transient yet enduring nature. The novel touches on themes like ecology, persecution, memory, mental health, and the history of the Yazidis, a Kurdish-speaking religious group indigenous to Kurdistan. There’s much to admire: the philosophical depth, the vivid portrayal of 1840s London, the educational exploration of the Yazidi experience, and Shafak’s stunning paragraphs.

📚 Arturo’s Island by Elsa Morante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein (1957, published in English in 1959).

During a visit to a Milan bookstore, I asked a chic bookseller for recommendations on Italian women authors with translated works. She rolled her eyes at the mention of Elena Ferrante and insisted that Elsa Morante was the one to read. My introduction to Morante was Arturo’s Island, a stunning novel and by far one of my favourite reads of the year.

The story follows Arturo, a teenage boy living in near isolation on a Neapolitan island. With a deceased mother and a father who is often absent, Arturo leads a solitary life until his father returns with a new, much younger wife. This sudden intrusion into his world introduces a host of new emotions, anxieties, and existential questions. While the blurb captures the basics, it doesn’t do justice to the novel's rich, fable-like depth, full of jealousy, drama, and poignant character development. A must-read for anyone interested in Italian literature.

Other notable favourites: All Fours by Miranda July, Pavilion of Women by Pearl S. Buck, Matrix by Lauren Groff, Boulder by Eva Baltasar (translated from the Catalan by Julia Sanches), Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi (translated from the Arabic by Sherif Hetata), Tongueless by Lau Yee-Wa (translated from the Chinese by Jennifer Feeley), and Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga.

Memoirs & Biographies

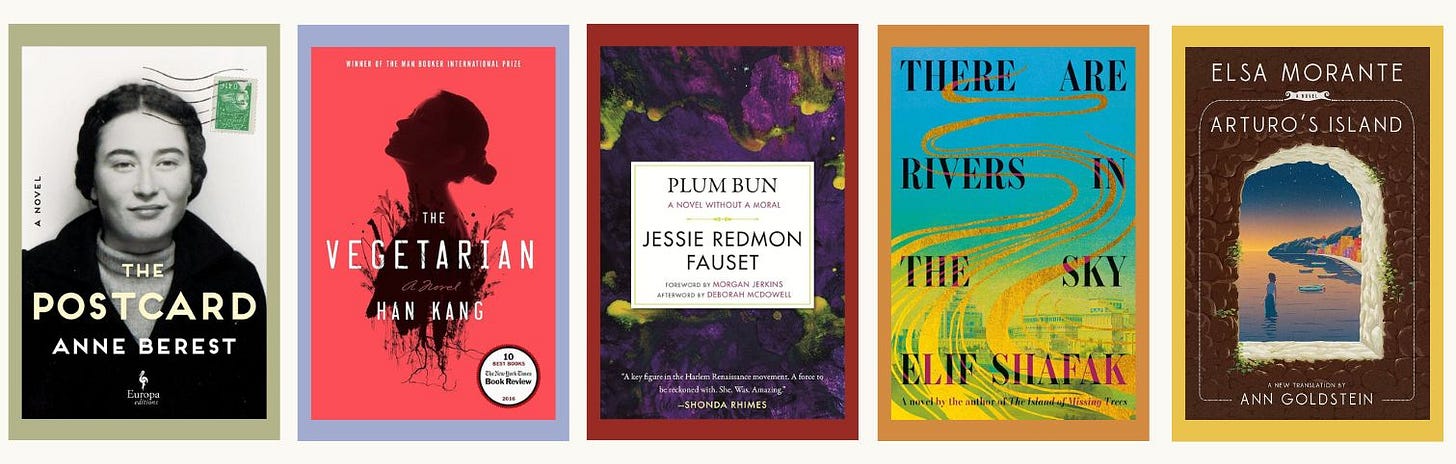

📚 In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations by Merilee Grindle (2023).

A compelling biography that places the pioneering work of Zelia Nuttall at the heart of Mexico’s archaeological and cultural rediscovery in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Nuttall, an often-overlooked figure in the field, was instrumental in advancing the study of pre-Columbian civilizations, particularly the Aztecs. Grindle’s research and storytelling breathe life into Nuttall’s intellectual journey, charting her exploration of Mexico’s ancient ruins and her role in challenging prevailing colonial perspectives that dismissed Indigenous history. This biography illuminates Nuttall’s contributions and highlights the broader cultural and political currents of her time, offering a nuanced view of her place in the history of Mexican archaeology.

Grindle deftly navigates the complexities of Nuttall’s work, balancing an appreciation for her groundbreaking scholarship with an honest reflection on the limitations and challenges she faced as a woman in a male-dominated academic field. The narrative provides an insightful look at how Nuttall's work in Mexico intersected with both the rise of nationalist sentiment in the country and the evolving field of archaeology. Through Nuttall’s story, the book explores broader themes of intellectual legacy, cultural appropriation, and the reclaiming of Indigenous history.

📚 How to Say Babylon by Safiya Sinclair (2023).

A vivid memoir of growing up in Jamaica under the rigid influence of her Rastafari father, Djani, and his fundamentalist views on purity, womanhood, and colonialism. The story is anchored in Sinclair’s childhood in White House, where she navigates a tense, often suffocating environment where cultural expectations collide with the rebellious stirrings of her own identity. Her father’s stern decrees and his perception of women as either virtuous or “Jezebel” figure into Sinclair’s complex coming-of-age, in which she grapples with her body, beliefs, and burgeoning creative spirit. The narrative feels like a slow burn, its tension and emotional depth palpable as Sinclair charts the development of her inner world amid a stifling exterior.

The book is an eloquent and, at times, heartbreaking exploration of Sinclair’s evolution from a dutiful daughter to a defiant poet, all while uncovering the often painful fractures within her family. Through lush prose, Sinclair paints a portrait of a divided home—her father’s artistic ambition is in conflict with his authoritarian grip, while her mother, despite her silence, instigates shifts of quiet rebellion. Sinclair’s intellectual pursuits, fueled by books and her thirst for knowledge, contrast with the physical and emotional confines of her upbringing. Yet, amid the harshness of her environment, she finds solace in words—both in the writings of poets like Sylvia Plath and in her own emergent voice. This memoir is a brilliant act of self-exploration and defiance, confronting the legacies of colonialism and patriarchy, and offering a nuanced, layered reflection on family, art, and freedom.

📚 Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner by Natalie Dykstra (2024).

I savored this biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner over several weeks, torn between never wanting it to end and finding it hard to think about anything else. The research is so thorough that I felt utterly immersed in her world, from the precise prices she paid for works of art decades ago to the emotional highs and lows of her extraordinary life. It’s a captivating journey into the heart of a woman whose legacy continues to shape the cultural landscape, particularly through the renowned museum she founded in Boston, which remains a testament to her vision.

Before reading the biography, my understanding of Gardner was vague at best, though I visited her namesake museum in Boston earlier this year. Anyone who steps inside is struck by her unparalleled art collection and bold cultural vision, and my appreciation for both deepened dramatically while reading. Gardner was an individual of immense privilege, yet her ambition, intellect, and passion made her a true Renaissance woman—one I’d invite to dinner (if I could). Dykstra not only paints a portrait of a woman who defied convention but also offers insight into the complexities of her character, revealing both her personal struggles and her larger-than-life achievements.

For Christmas, I received a book that curates her travel journals, a window into the mind of a fascinating and inspiring woman who truly lived for art, culture, and the pursuit of beauty.

📚 Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country by Patricia Evangelista (2023).

Covering the years between 2016 and 2022, when Rodrigo Duterte served as president of the Philippines, Some People Need Killing is a harrowing and impactful account of the extrajudicial killings that unfolded during his "war on drugs." Acclaimed journalist Patricia Evangelista combines meticulous reportage with compelling storytelling to uncover the experiences of the victims, their families, and even the perpetrators, shedding light on a deeply unsettling chapter in the nation’s history. Her deep empathy and sharp eye for detail allow the stories to transcend the statistics, bringing a human face to the unimaginable toll the violence took on communities.

Before reading, I was unaware of the full scale of Duterte's campaign and the extraordinary violence that erupted under his rule. Evangelista's unflinching approach forces the reader to confront the brutality of the state-sanctioned killings while questioning the moral justifications that fuel such acts. The book offers an essential and complex look at this dark period in the Philippines' modern history, revealing not only the consequences of authoritarian rule but also the intricate web of politics, corruption, and societal division that sustains it. While difficult to digest, Some People Need Killing is a necessary and sobering examination of power and its human cost.

📚 A Woman in the Polar Night by Christiane Ritter, translated from the German by Jane Degras (1938, published in English in 1954).

One of my most recent reads, this captivating memoir offers a rare and intimate glimpse into life in the Arctic. First published in 1934, it recounts Ritter’s experience living with her husband in a remote Norwegian outpost, enduring the harsh polar nights and extreme isolation. Through her lyrical prose, Ritter paints a vivid picture of the raw beauty and desolation of the Arctic landscape, capturing the struggle to reconcile the vast emptiness of nature with the richness of her inner world. Her reflections on solitude, nature, and human endurance resonate with timeless relevance.

The book beautifully conveys Ritter’s complex emotions and intellectual curiosity during her months of solitude. Rather than simply focusing on the stark physical challenges, Ritter delves into a deeper, philosophical meditation on isolation, the passage of time, and the vastness of the natural world. A Woman in the Polar Night is a quiet yet profound exploration of the human spirit’s capacity to adapt and reflect in the face of extreme conditions, making it a must-read for those captivated by the interplay between landscape and self.

Other notable favourites: My Life on the Road by Gloria Steinem, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and my fight against the Islamic State by Nadia Murad, and I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself: One Woman’s Pursuit of Pleasure in Paris by Glynnis MacNicol.

Non-Fiction

📚 Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala by Stephen C. Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer (1982).

A heavily researched and compelling narrative of one of American foreign policy's most consequential covert operations. The book chronicles the 1954 CIA-led coup that overthrew the democratically elected Guatemalan government of Jacobo Árbenz, a pivotal moment in the Cold War that reverberated through Latin America for decades. The authors weave together a rich tapestry of historical details, drawing from extensive interviews and declassified documents to illuminate the motivations behind the U.S. intervention and the devastating consequences it had for Guatemala’s people and their future. The authors’ analysis of the geopolitical and economic factors at play, particularly the influence of the United Fruit Company, offers valuable insight into the complex interplay of corporate interests, U.S. politics, and international power struggles.

What makes Bitter Fruit particularly striking is its human focus—the book does not simply recount the mechanics of the coup but also examines the lasting social and political ramifications for the Guatemalan people. The authors highlight the personal stories of those caught in the maelstrom of U.S. interference, including the suffering of ordinary citizens, the political chaos that followed, and the long-term instability that plagued the country.

📚 Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul by Taran N. Khan (2019).

Through her detailed observations and evocative prose, Khan takes readers on a poignant journey through Kabul, chronicling her experiences as she navigates the streets of the Afghan capital in the years following the fall of the Taliban. A self-proclaimed outsider, Khan uses her role as a foreign journalist to delve deeply into the lives of those who have borne the brunt of decades of conflict, from daily commuters to street vendors, offering a layered and complex portrait of a city in constant flux. Her careful attention to the subtleties of life in Kabul—the ordinary moments, the quiet resilience of its people—imbues the narrative with both empathy and insight.

Khan portrays Kabul not just as a war-torn city but as a living, breathing entity with a rich cultural history and an enduring sense of possibility. Her reflections on the tension between modernity and tradition, the resilience of women, and the shifting sands of identity in post-war Afghanistan provide a powerful framework for understanding the city's intricate dynamics. Khan’s voice is one of quiet authority, not an outsider’s judgment but rather a respectful engagement with the complexities of a place too often reduced to stereotypes.

📚 A Bookshop of One’s Own: How a group of women set out to change the world by Jane Cholmeley (2024).

To found and run a feminist bookshop—now that’s the dream. Jane Cholmeley did just that when she co-founded Silver Moon Women’s Bookshop in London in 1984. It grew to become the largest of its kind in Europe, putting women’s writing front and centre on the renowned Charing Cross Road. Cholmeley’s account of the bookshop’s 17 years in operation offers a candid look at the challenges of running a feminist enterprise amid financial hurdles, bureaucratic red tape, and a society still resistant to feminism and LGBTQ+ topics. Add to that the rise of corporate bookstores, and Silver Moon’s survival became even more remarkable.

What makes this book such a fascinating read is its layers. Cholmeley’s dedication to championing women’s writing—still a marginalized field today—is awe-inspiring. She also pulls back the curtain on the day-to-day of running a bookshop: the finances, the logistics, the successes, and the failures. There are wonderful anecdotes of women writers visiting the shop, the events they hosted, and some unforgettable window displays. The book also introduces many 1980s and '90s women writers, making it a treasure trove for those eager to expand their literary horizons. We owe so much to women like Cholmeley; this book is a fitting tribute to their vision and determination. A must-read indeed.

📚 The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Liang (2024).

Rooted in the personal yet branching into the universal, Laing’s latest work is a seamless blend of memoir and cultural history. It begins with Laing and her husband restoring an 18th-century walled garden in Suffolk during the lockdown of 2020. This project serves as the book’s narrative spine, chronicling the toil, discovery, and joy involved in bringing a forgotten space back to life. Yet the book’s real brilliance lies in its cultural exploration: Laing delves into gardens as symbols of beauty, power, and refuge, weaving in stories from literature, history, and philosophy.

Among the many gems Laing unearths, a few stand out: an Italian garden turned wartime sanctuary, William Morris’s utopian dream of a communal Eden, and the linguistic roots of “paradise” in ancient Persia. Her prose brims with an infectious curiosity, each chapter a doorway to an unexpected revelation. From the costs of cultivation to the solace gardens offer in turbulent times, Laing invites readers to see these green spaces as reflections of humanity itself—fragile, resilient, and endlessly fascinating. Whether you’re a gardener or merely a dreamer, this book will deepen your appreciation for the common paradise we all share.

📚 The Bluestockings: A History of the First Women's Movement by Susannah Gibson (2024).

I started reading this book the very day it was published—July 23rd—because a history of the first women’s movement is exactly the kind of subject that excites me. The Bluestockings, a group of English women in the late 1700s, challenged the societal norms that denied women the right to think, read, write, or contribute meaningful dialogue at dinner tables. In an era when education was thought to undermine a woman’s suitability as a wife, these women boldly championed the belief that some women were just as capable of intellectual pursuits as men.

This book delves into the lives of these trailblazing women, detailing their challenges, inspirations, and the choices that society deemed scandalous at the time. Passionate about learning, reading, and writing, they defied the gender norms of their day, leaving an indelible mark on a male-dominated society. Virginia Woolf regarded their rise as one of history’s most significant moments, likening it to events like the Crusades or the Wars of the Roses. I cannot recommend this book enough—it's an incredible tribute to these remarkable women and their lasting legacy.

Other notable favourites: Divine Might: Goddesses in Greek Myth by Natalie Haynes, The Quickening: Creation and Community at the Ends of the Earth by Elizabeth Rush, Until I Find You: Disappeared Children and Coercive Adoptions in Guatemala by Rachel Nolan, A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by Mary Ann Glendon, A Life of One's Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again by Joanna Biggs, and Private Revolutions: Four Women Face China’s New Social Order by Yuan Yang.

What were your favourite books of the year? What are you excited to curl up with in January?

Jennifer

xxx