On Bremerhaven: A City Of Exports, Emigration, And German Poverty

A travel piece from the archives.

On the banks of the River Weser in north-western Germany lies the city of Bremerhaven (whose name translates literally to “Bremen’s harbor”). Technically a part of the city-state of Bremen, which is located an hour by train to the south, this area has long been a major trade port. Today, Bremerhaven imports and exports more cars than any other European city.

In contrast to the number of cars, Bremerhaven doesn’t tend to receive too many visitors.

When I was leaving Hamburg to go to Bremen, people kept asking, “Why Bremen?” and when I was leaving Bremen to go to Bremerhaven, people (with an even more alarmed look on their faces) would ask, “Why Bremerhaven??”. My destinations were gradually getting smaller and seemingly more bizarre.

I did have a reason, though. Bremerhaven is home to Europe’s largest theme museum about emigration — The German Emigration Center — a place that seemed intriguing enough to warrant a couple of days jaunt up north.

The train ride took less time than Google Maps initially said it would, and so I arrived a few minutes earlier than my Couchsurfing host, who had kindly offered to pick me up from the station after he had finished work. He greeted me with a warm smile and then exclaimed: “That’s not a small suitcase!!!”

My Whatsapp description of my luggage situation had been interpreted differently. “Well, it isn’t a carry-on, but it also isn’t my biggest suitcase,” I responded. We squeezed the suitcase into the back of his car and then again into his kitchen, where I would sleep on a thin mattress on the floor for the next three evenings.

Before I was welcomed into his home, we took the drive home as an opportunity to get to know each other. An activity that was interrupted by a pizza delivery man with some of the worst driving skills imaginable. The two of us laughed about his weaving and awful impatience for the majority of the ride.

Once the slightly large suitcase had been shown to its kitchen position, he changed his shoes, and then we headed out to see the sights of Bremerhaven before it got dark.

There are no better people than those who are passionate about where they live and who take the time to understand the local history and culture. Despite only being in Bremerhaven for about a year, my host had thrown himself into learning about his new home and was full of fun facts and peculiar anecdotes about the area.

Our walking tour started with a stroll down the promenade that runs the length of the port. Ten minutes in, it began to drizzle, but we continued.

During our walk, we passed the Klimahaus Bremerhaven 8° Ost, which takes visitors on a journey through the world’s various climatic zones, and The German Maritime Museum, dedicated to the history of seafaring and possesses the wreck of a 1380 Hanseatic cog as its centerpiece. And let’s not forget the Wilhelm Bauer, where you can step inside a decommissioned Nazi U-boat. These are the main attractions in the city. However, I was particularly entertained by an indoor mall that looked like a bootlegged version of The Venetian in Las Vegas (which itself resembles Venice, Italy).

I was mostly struck by how empty the streets were, a shock that only intensified when I realized we were walking down the main road of the city center. Despite this being my sixth trip to Germany, I had never before seen this sector of the country—a modest and economically impoverished locale.

Bremerhaven used to be prosperous but has now earned the unwelcome nickname of the “poorest neighborhood in Germany.” The state of Bremen (comprising Bremen and Bremerhaven) is both the smallest and the poorest in the country.

From the outside, German poverty sounds like an oxymoron. After all, this is one of the world’s wealthiest countries with one of the highest average incomes in the European Union. But, in Bremerhaven, where there are almost no job opportunities, you would be hard-pressed to believe it.

On our first evening, we went for a doner kebab at a sit-down restaurant. Our waitress was so surprised that someone was speaking English that she thought that I was making fun of her. She didn’t believe that there was just someone in the restaurant who couldn’t speak German, as that would mean someone from the outside had come in.

Bremerhaven is more used to letting its people go.

From their harbor, between 1830-1974, 7.2 million emigrants left to sail to the New World. In the 19th century, 90 percent of the emigrants from Bremerhaven went to the U.S.A., and 70 percent of those arrived in New York. In the years leading up to 1875, there were virtually no obstacles or restrictions for immigrants entering the United States.

In 2007, the German Emigration Center won the European Museum of the Year Award for its innovative and interactive presentation of 300 years of German migration history and its emotional approach to the subject of emigration.

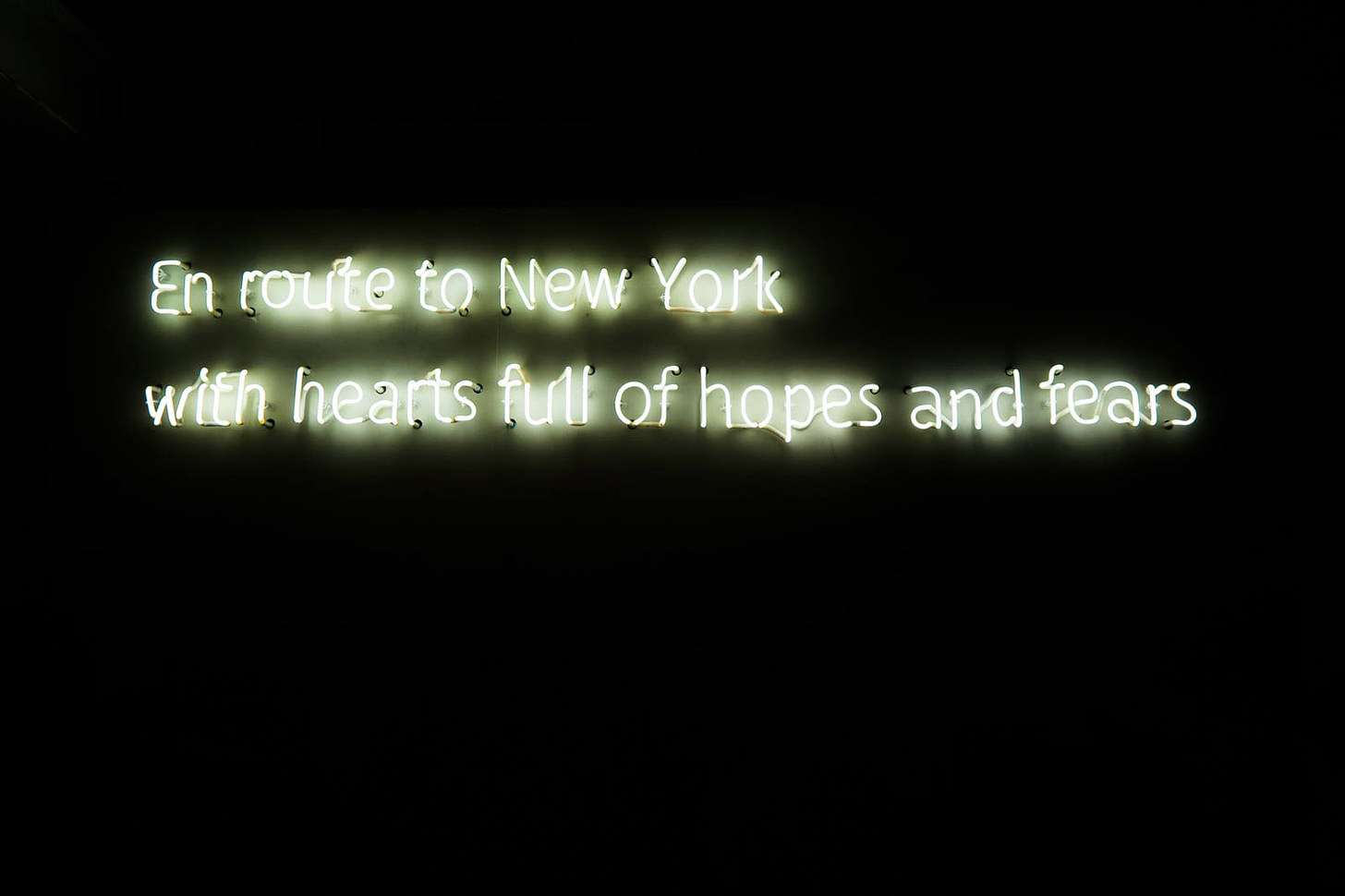

You begin by receiving an electronic boarding pass that contains the story of an individual who emigrated to the New World. Throughout the exhibit, you follow this individual’s account, giving you a thoroughly personal and emotional experience. Starting at the wharf with the other passengers who are huddled together, you then board the ship and navigate your way through cramped and creaky sleeping and dining cabins to learn about the three phases of ship technology that crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

Once you make it to Ellis Island, you take a quiz to see if you are allowed to enter the US, and if you pass, you will find yourself in Grand Central Station — ready to start your new life.

The second section of the museum is dedicated to those who emigrated, complete with a 1970s-era shopping mall and a retro movie theatre showing short films about German emigrants and their families. The museum also provides access to two international online databases where you can try tracing your German forebears.

I had traveled to Bremerhaven specifically to see this museum, so I had an inkling I would enjoy it, but I wasn’t prepared for just how spectacular it was. Given I immigrated to the US and my ancestors emigrated from Germany to England, the museum felt incredibly personal. On the boat, I stood in silence, imagining my family cramming themselves into the cramped steerage quarters that were the norm up through the 1870s.

I teared up learning about “my person,” Hertha Nathorff, who departed Bremerhaven for New York on April 28th, 1939, due to being Jewish and was never again able to work as a doctor, nor did she ever return to Germany. Instead, she died in New York in 1993 at the age of 98. Always bitter about being an immigrant, in 1971, she wrote that “looking back, she would have preferred being gassed in a concentration camp.”

Homesickness lasted her entire lifetime, and despite becoming an American citizen, she only ever considered herself German. For the vast majority of those immigrants, the purpose of the journey is to “make a better life.” A mission that ties the first immigrants to board a ship to the US with my family, who (more conveniently) just hopped on a plane.

While the mechanics of immigration to the US have changed—it is a lot easier to transport yourself there, but it is a lot harder to be let in—people's ambitions and objectives remain the same.

As I walked back through the mainly desolate city center to where I was staying, I couldn’t help but think how the stories of hope in The German Emigration Center contrasted vastly with the feelings that I was picking up from the present-day city.

I stopped to get a coffee at Brotbar and recognized the barista from the previous day. We started talking, and she excitedly told me that in a couple of months, she would be in a position to move to a bigger city — Bremen, in this case — to be able to pursue a career in tourism management. “There aren’t many opportunities around here,” she continued. “For me to have a career, I have to move somewhere new.”

“That is exciting!” I said.

“I am a little nervous,” she admitted.

“Have you been to The German Immigration Center?” I asked. She hadn’t, so I told her that I thought it would be worth a visit for her to see how other people had been able to pick up and leave. “You won’t feel so alone.”

That evening, all I could think about was hope and courage—the two things that every immigrant needs but doesn’t realize they possess until they find themselves halfway to their new world.

Originally written in May 2018.